BJP’s gain in 2014 and the collapse of Congress and Left

BJP From the time of Jan Sangh — 1951 to 1971 — to BJP’s first election in 1984, the party had a low conversion ratio of votes into seats. Its vote share was always higher than its seat share. In 1984, it got 7.4% of the votes and 0.4% of the seats. From the next election onwards, when it crossed 11% of votes — which might be near the party’s seat conversion threshold — it saw a dramatic increase in seats.

From 1989 onwards its seat share was always higher than vote share. Between 1984 and 2014, the party peaked in 1998-99, when it got around 24-26% of the votes and 34% of the seats. The next dramatic jump came in 2014. From 18.8% in 2009, vote share increased by 12.5 percentage points to reach 31.3%. Share in seats, however, improved by more than 30 percentage points — from 21.4% in 2009 to 51.9% in 2014.

Cong Congress, on the other hand, went on a different trajectory. In 2009, the party had got 28.6% of the votes and won 37.9% of the seats. In the next election, its vote share declined by 9 percentage points while seats came down by almost 30 percentage points. Despite getting around 20% votes in 2014 and 2019 – which seems to be lower than the party’s threshold – the party got less than 10% of the seats, indicating that seats alone are no benchmark to understand its ground presence.

Left Between 2004 and 2009, the Left’s vote share increased by 0.4% while seats increased by 3.1%, indicating that for that election the party’s threshold was between 7% and 8% of votes. In the next election, the party saw a 0.6 percentage point dip in its vote share but the seat share came down by 6.4 percentage points.

TMC gained 0.4% votes, lost 12 seats…

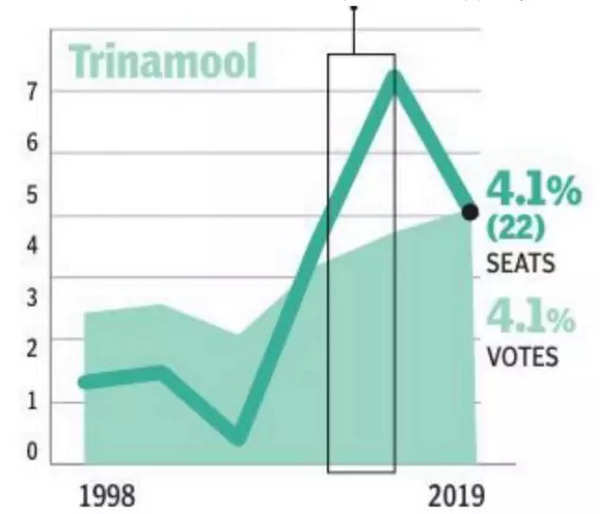

Trinamool Congress’ vote and seat shares show an interesting trend. Between 2004 and 2009, its vote share increased by 1.1 percentage points while seat share saw a 3.1 percentage point rise.

For these elections, which were multi-cornered between the Left, Trinamool and Congress, the party’s threshold might be around 3% votes, and hence a small jump in votes gave a disproportionate gain in seats. Elections in West Bengal kept on becoming two-cornered, which might have pushed the threshold vote share. Between 2014 and 2019, when the election was between BJP and Trinamool, the party’s vote share increased by 0.4 percentage points while its seats dropped by 2.2 percentage points.

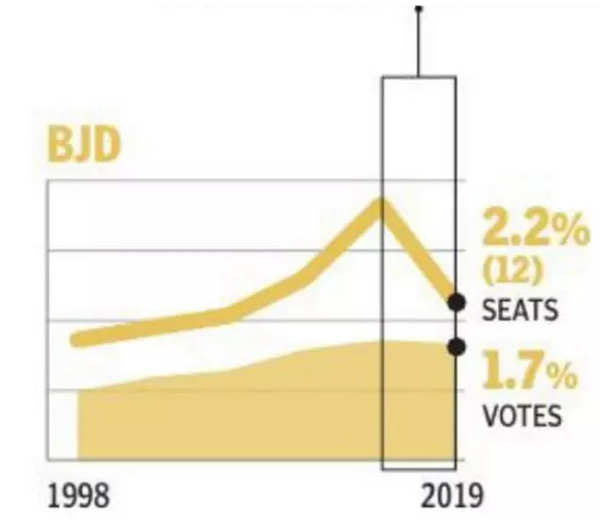

Similarly, BJD’s vote share remained the same between 2014 and 2019 but the party lost eight seats as the contest became more bipolar.

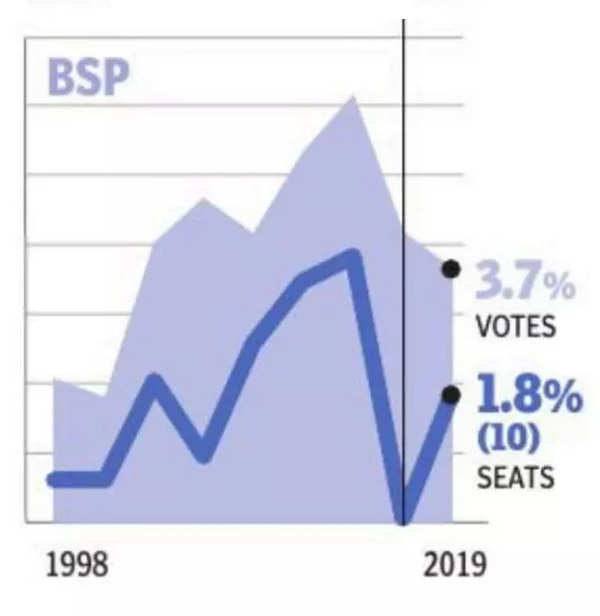

…but BSP lost 0.5% votes, yet gained 10 seats

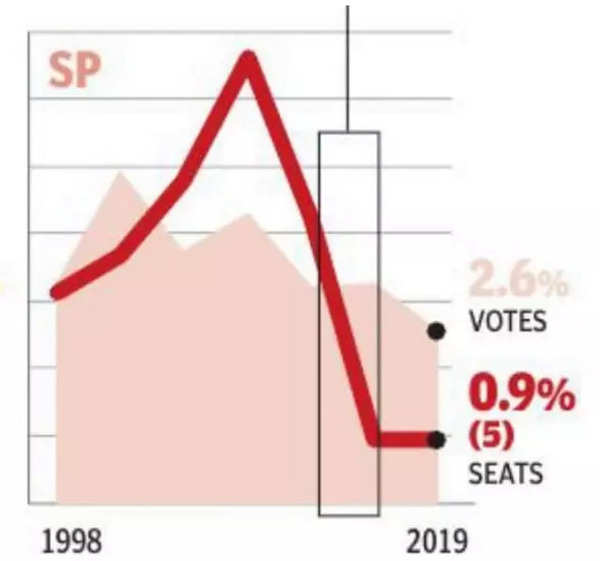

Samajwadi Party saw a slight increase in its vote share but lost 18 seats between 2009 and 2014 because of a similar reason.

BSP, on the other hand, has a slightly different story. In 2014 it got 4.2% of votes and 0 seats. In 2019, its vote share declined but seat share increased. This happened because it contested fewer seats as it had allied with SP.

Fence-sitting voters are the real sultans of swing

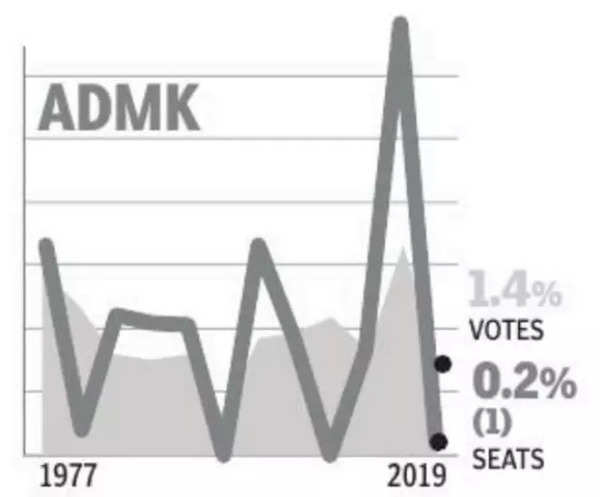

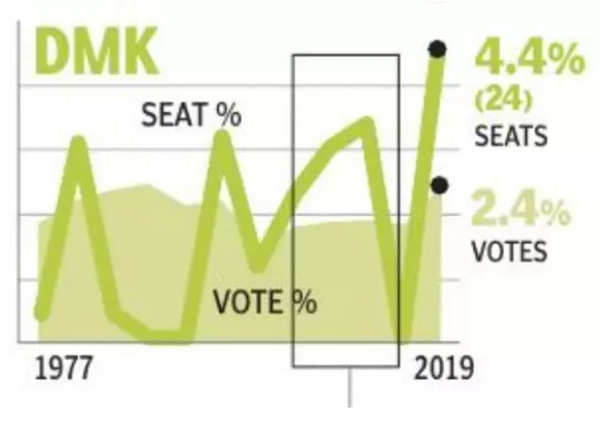

For many parties like DMK and ADMK, the dedicated voters remain loyal as their vote share remains constant but seats might change dramatically. This could be because fence-sitting voters with no committed loyalty to DMK or ADMK switch votes in different elections. For instance, in the 2004, 2009 and 2014 LS elections, DMK’s vote share remained constant at 1.8% while its seats changed from 16 to 18 to 0 in the three elections.

In 2019, its vote share increased by 0.6 percentage points while its seats increased by 4.4 percentage points. Similarly for ADMK, between 2009 and 2014, the vote share increased by 1.6 percentage points while the corresponding increase in seat share was more than 5 percentage points.