NEW DELHI: In validating Section 6A of the Citizenship Act that conferred citizenship to Bangladeshi migrants entering India before March 25, 1971, Chief Justice D Y Chandrachud in his opinion said this cut-off date was reasonable as on that day Pakistan army had launched ‘Operation Searchlight‘ to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in then East Pakistan.

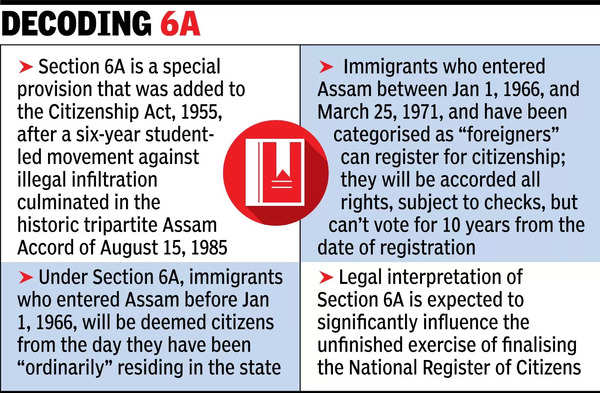

Agreeing with the majority opinion of Justices Surya Kant, M M Sundresh and Manoj Misra on the validity of Section 6A incorporated in the Citizenship Act to honour the Centre’s commitment under the 1985 Assam Accord signed with students’ unions, CJI Chandrachud said application of the provision only to Assam had a reasonable nexus with the magnitude of the problem faced by the state due to unabated influx of illegal migrants from Bangladesh.

Quoting M Rafiq Islam’s book ‘A Tale of Millions: Bangladesh Liberation War, 1971’, the CJI said, “On March 25, 1971, the Pakistan army launched Operation Searchlight to curb the Bengali nationalist movement in East Pakistan. The migrants before the operation were considered to be migrants of partition towards which India had a liberal policy. Migrants from Bangladesh after the said date were considered to be migrants of war and not partition. Thus, the cut-off date of March 25, 1971, is reasonable.”

Referring to migrations from Bangladesh to India immediately after partition, the CJI said, “Since the migration from East Pakistan to Assam was in great numbers after the partition of undivided India and since the migration from East Pakistan after Operation Searchlight would increase, the yardstick has nexus with the objects of reducing migration and conferring citizenship to migrants of Indian origin (that is person born in undivided India).”

Justice Chandrachud referred to the Sarbananda Sonowal judgment expressing concern over Assam facing “external aggression and internal disturbance” due to largescale illegal migration from Bangladesh and rejected the challenge to Section 6A’s validity based on the provision’s application only to Assam even though West Bengal, Meghalaya, Tripura and Mizoram shared longer borders with Bangladesh and faced illegal migrant influx.

“Though other states such as West Bengal (2,216.7 km), Meghalaya (443 km), Tripura (856 km) and Mizoram (318 km) share a larger border with Bangladesh as compared to Assam (263 km), the magnitude of influx to Assam and its impact on the cultural and political rights of Assamese and tribal populations is higher,” he said.

“The data submitted by the petitioners indicates that the total number of immigrants in Assam is approximately 40 lakh, 57 lakh in West Bengal, 30,000 in Meghalaya and 3,25,000 in Tripura. The impact of 40 lakh migrants in Assam may conceivably be greater than the impact of 57 lakh migrants in West Bengal because of Assam’s lesser population and land area compared to West Bengal,” the CJI said.

The petitioners, challenging the validity of Sec 6A, had argued that largescale entry of illegal migrants from Bangladesh and conferring them citizenship had jeopardised Assamese people’s fundamental right to protect and conserve their culture.

Rejecting this argument, the CJI said, “First, as a matter of constitutional principle, the mere presence of different ethnic groups in a state is not sufficient to infringe the right guaranteed by Article 29(1)… Second, various constitutional and legislative provisions protect Assamese cultural heritage.”