The Western mind has always struggled with quantum physics, much like it has with paganism, never quite able to decipher how a particle can also be a wave or vice versa. This difficulty is, at its core, a language problem—perhaps even a side effect of Abrahamic thought—which may explain why its brightest minds, such as Oppenheimer, are often drawn to Vedanta. This dichotomy is evident in reactions to the statue of Lord Shiva at CERN, the world’s most advanced particle physics laboratory and home to the Large Hadron Collider. The statue, depicting Lord Shiva performing the cosmic dance, often confounds visitors, with more narrow-minded ones demanding its removal for being “anti-science.” Nothing could be further from the truth, as the dancing form symbolises both creation and destruction—the cosmic dance that dictates the flow of the universe.

As Fritjof Capra, the Western pioneer in finding parallels between Eastern mysticism and modern physics, wrote in The Tao of Physics preface:

“As I sat on that beach, my former experiences came to life; I saw cascades of energy coming down from outer space, in which particles were created and destroyed in rhythmic pulses; I saw the atoms of the elements and those of my body participating in this cosmic dance of energy; I felt its rhythm and I heard its sound, and at that moment, I knew that this was the Dance of Shiva, the Lord of Dancers worshipped by the Hindus.”

It is no surprise, then, that the statue—gifted by the Indian government and unveiled on 18 June 2004—bears a quote from Capra, explaining: “Hundreds of years ago, Indian artists created visual images of dancing Shivas in a beautiful series of bronzes. In our time, physicists have used the most advanced technology to portray the patterns of the cosmic dance. The metaphor of the cosmic dance thus unifies ancient mythology, religious art, and modern physics.”

The Dance of Shiva

The statue captures Shiva performing the Tandava, a dance believed to be the source of the cycle of creation, preservation, and destruction. The dance exists in five forms, representing the cosmic cycle from creation to dissolution:

- Srishti – creation, evolution

- Sthiti – preservation, support

- Samhara – destruction, evolution

- Tirobhava – illusion

- Anugraha – release, emancipation, grace

The significance of the Tandava extends beyond mythology, resonating deeply with artistic and scientific thought alike. The dance embodies the perpetual motion of the cosmos, where matter is never static but constantly shifting between states, much like the subatomic world described by quantum mechanics. In this eternal rhythm, destruction is not an end but a necessary transition for renewal, mirroring the natural laws governing energy and matter.

One of the most remarkable encounters with the Nataraja took place in early 20th-century Chennai (then Madras), where an elderly European gentleman stood mesmerised before a 12th-century bronze in the city’s state museum. As he gazed at the sculpture, he entered a trance-like state and began to mimic Shiva’s dance, his arms and legs moving in rhythm with the cosmic energy captured in bronze. The sight baffled museum guards and patrons, who gathered to watch the unusual spectacle. Concerned by the disturbance, the curator arrived, prepared to have the foreigner removed—until he realised the man was none other than Auguste Rodin, one of the most celebrated sculptors of all time. Overcome with emotion, Rodin later described the Nataraja as “one of the greatest works of art ever created by the human mind.”

Rodin’s awe stemmed from the sculpture’s ability to capture both movement and stillness simultaneously—Shiva’s limbs flail outward in a centrifugal explosion of energy, yet his face remains serene, embodying a paradox at the heart of existence. It is this fusion of dynamism and poise, chaos and order, that makes the Nataraja not just a religious icon but a profound metaphor for the dance of the universe itself.

As V. S. Ramachandran wrote in Phantoms in the Brain: “You don’t have to be religious or Indian or Rodin to appreciate the grandeur of this bronze. At a very literal level, it depicts the cosmic dance of Shiva, who creates, sustains, and destroys the Universe. But the sculpture is much more than that; it is a metaphor of the dance of the universe itself, of the movement and energy of the cosmos. The artist depicts this sensation through the skilful use of many devices. For example, the centrifugal motion of Shiva’s arms and legs flailing in different directions and the wavy tresses flying off his head symbolise the agitation and frenzy of the cosmos. Yet, amid this turbulence—this fitful fever of life—Shiva remains serenely composed, gazing at his own creation with supreme tranquillity and poise.”

CERN’s Cosmic Paradox

The juxtaposition is no accident. The Shiva statue at CERN is more than a cultural artefact. It stands as a silent acknowledgment of something physics encounters at its very limits—the inescapable reality of paradox. The universe does not conform to the neat categories that science prefers. Matter and energy behave in unpredictable ways at the subatomic level.

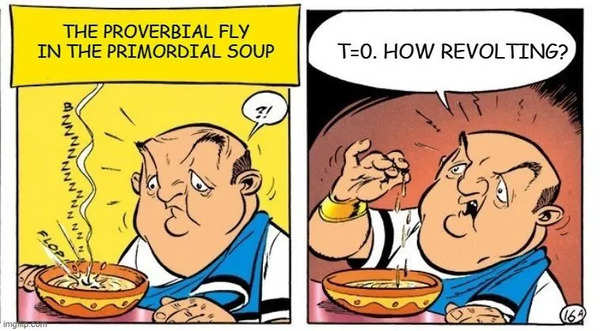

Time itself falters at T = 0, the precise moment of the Big Bang, as does the question of the primordial soup.

The prevailing theory suggests that self-replicating, complex amino acid-based compounds somehow emerged from the primordial soup of water and chemicals, possibly triggered by a fortuitous lightning strike. However, much like the Big Bang theory can describe events for T > 0 but cannot explain what happened at T = 0, the origin of life at T = 0 remains beyond the reach of current scientific understanding. In this sense, T = 0 is the proverbial fly in the primordial soup.

Even if we set aside sentience—the point at which even a microbe could make a choice between two degrees of freedom—how did cells organise themselves into life forms?

CERN, in its quest to decode the universe, is confronting a problem that isn’t just scientific—it is existential. And so, right outside its most ambitious experiment, stands Shiva, the cosmic dancer, as if to remind scientists that the universe is not built on rigid equations alone, but on movement, rhythm, and uncertainty.

The T = 0 Problem

The Large Hadron Collider (LHC) is designed to recreate conditions as close as possible to the Big Bang—but it cannot go all the way back. Scientists can model events occurring after T > 0, the moment when the universe began expanding. But T = 0—the singularity itself—remains elusive.

The challenge is fundamental. General relativity, which governs large-scale physics, and quantum mechanics, which governs the smallest scales, do not align at this point. The mathematics collapses into infinity. The equations break down. Physics, as we know it, ceases to function.

It is an unsettling realisation: even at the height of human knowledge, we cannot explain our own beginning. The deeper we probe, the more the answer slips through our grasp. The moment before the universe—the event that created time itself—remains beyond our grasp. This is where Shiva’s cosmic dance becomes more than a metaphor.

Quantum Mechanics and the Dance of Shiva

Shiva’s Tandava, his eternal dance, represents the fundamental forces that drive the universe—creation, preservation, and destruction—all happening simultaneously. It is a cosmic process, one that echoes not only the grand scale of the universe but also the strange, counterintuitive world of quantum mechanics. In quantum mechanics, nothing is static. An electron is not a fixed entity but a probability wave. A vacuum is not empty but a seething sea of virtual particles flashing in and out of existence. At its most fundamental level, the universe is not a place—it is a process.

This is where Professor V. Balakrishnan, a distinguished physicist from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Madras, adds another layer to the discussion. A renowned expert in theoretical physics and chaos theory, he explains the failure of classical language to describe the quantum world:

“These terms are meaningless when explained in classical language. The failure isn’t on the part of the quantum mechanical particle, but on the part of our language itself.”

CERN’s Shiva: A Cosmic Reminder

The Shiva statue at CERN stands as a reminder that the universe is not static—it is a dance. A dance of forces, particles, and energy. A dance where creation and destruction are not opposites but part of the same process. Science may yet find the answer to T = 0. It may unlock the final secrets of the universe. But even then, one truth will remain: The dance will go on.