In that moment where the wearied, snorting giant saw immortality slipping from his grasp, George Foreman snapped at his trainer Angelo Dundee, left the stool, and rushed to the centre groping for greatness.

It was unlike Foreman who had long evolved from a mercurial heavyweight to a genial preacher, the depression induced by the defeat at the hands of an aging Ali in the “rumble in the jungle” having sent him sliding down a slope, to self-flagellation, continuing to throw arms in the ring, to insist he was a man, before hitting the rock bottom and finding the God and the Gospel. In his rebirth, he had left the ‘life in the fast lane’ of glitz, greenbacks and girls, that’s the lot of testosterone-driven champion pugilists. It was church and preaching, calmness at the core. When he, broke, returned to the ring as a mean to garner money for his ‘youth centre”, he had thought of regaining the Title that he lost in Zaire, a fantasy that lurks in every retired boxer, and that drives all to take one last chance at greatness, that has made a joke of all the yesteryear champions – from Sugar Rays to Larry Holmes.

But in Foreman’s return, gone was the baleful glare and the snarling face. The Preacher was in the ring as if blessing his defeated opponents, and counting his own.

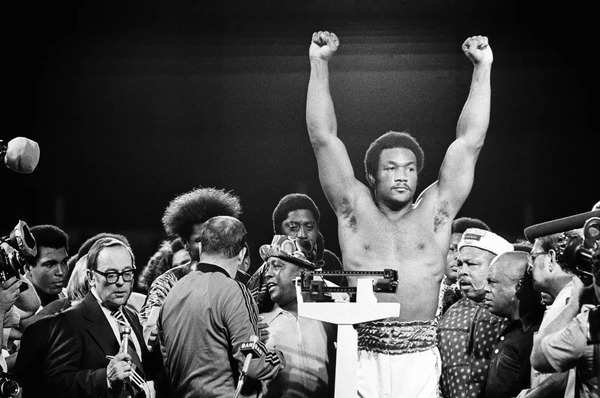

George Foreman, the fearsome heavyweight who became a beloved champion, dies at 76 (AP Image)

That was what surprised all around the arena watching the 42-year-old take on 19 years younger Michael Moorer on that 1995 evening, when he snapped at Dundee and left the corner in a rush of blood. Unknown to them, ‘Big George’ was angry at Dundee playing him for a greenhorn, employing the tactic that the trainer used on an un-trying and tired Sugar Ray Leonard to rouse him from his slumber into throwing machine gun bombs that made a mincemeat of Tommie Hearns and earned him victory. Since then, both Foreman and Dundee have revealed that the latter tried to din into his head that knockout was the only way to victory. “Its kind of this, you are behind on points” – the suggestion viewed as the catalyst for Leornard’s comeback was seen by Foreman as showing him up. “Don’t bring that up with me,” Foreman had snubbed.

What followed is part of the boxing lore, one of the greatest rounds in the history of heavyweight, written and executed by the portly performer. A desperate Foreman wanted a clear shot at Moorer’s head, for which he moved to the side that was a strict no-go – left hand of the young southpaw. He ignored the advice of Dundee, saw the full sphere of the head, threw a probing one-two. It was a reconnaissance mission. And then, the real one – boom, boom. Moorer went down, lifted his head in a daze, and slid back to defeat. Foreman kneeled in his corner, and prayed. He was wearing red shorts that had faded to pink, bearing ‘George Foreman, Heavyweight champion”, that he had worn in Kinshasha. He had in that moment exorcised the ghost of Zaire that had haunted him for 20 years. He was calm again. He was great again.

When Foreman left us all on a warm New Delhi Saturday, he went a happy man. One of his last tweets was his photographs surrounded by loving great grand kids in his Texas mansion, thanking life for the pleasure of family life and peaceful mind. Few of his fellow travellers had joyful retired life. Taking bombs to their heads round after round for years, they were damaged goods. Slurring speech, slow movements, trailing train of thoughts. Ali was the worst hit, afflicted by Parkinson’s and saddled with virtual paralysis for better part of his retirement. Foreman was always counting his blessings.

So, who was Foreman, the man who travelled from a promising boxer to a boxing immortal, a hedonist who became a messenger of God, an old man who became the face of the adage that ‘age is a number’?

Boxing greats Muhammad Ali, left, and George Foreman arrive at a Vanity Fair Oscar party in West Hollywood, Calif., on March 24, 1997. (AP Image)

Black sportsmen and women, boxers or baseballers or athletes or hoopsters, are slices of American history that trace the place of the race in a given era. The Jim Crow apartheid kept them apart from the mainstream, but the impassioned men could not give up their chosen pursuits. There emerged parallel sporting systems, like separate train wagons or smoking rooms for black and white. The Negro leagues had players and teams compete with the sheer dint of their talents, but did not find acceptance with the white-only mainstream. And then there were pioneers who broke the colour ceiling, because they could not be ignored. They brought along special skills that were not known to the whites, a dazzling style to the tough dreary arts. If there was Jack Johnson and Joe Louis in pugilism, there was Jackie Robinson in baseball, Jesse Owens and the likes on track. When Archie Moore was finally given an opportunity at the title in 1952, he swiftly, and artfully, despatched Joey Maxim to win the light heavyweight at the age of 36 (real 39). To his celebrating entourage, the Old Mongoose preached moderation. “I know it’s a matter of happiness. But let’s keep the perspective: I should have won it 5 years ago.” Such was the apartheid.

As the square ring, post-Rocky Marciano, became a coliseum of black gladiators, along came champions like Floyd Patterson, Sonny Liston, Mohd Ali, Joe Frazier, Foreman, Larry Holmes, and the list went on. They were all blacks, and no white measured up to their special talents. Even those who never won the title were greats, like Ken Norton and Ron Lyle. They fought amongst themselves and took boxing to its zenith.

But years before they became stars in the sky, they were all poor, runaway kids, felons, who found boxing as their calling, but also viewed it as their ticket out of the hell of ghettos. It is from such background emerged the growing boy, who would become the lean mean fighting machine. Foreman, as he progressed, came to be seen as the “hardest puncher” ever to step in the ring. After he worked the heavy bags, they famously bore big hole like depressions. Archie Moore, in Foreman’s corner in Kinshasha, said they felt Ali dying in the ring was a distinct possibility, and he prayed for his safety. Such became the boy who, in Jamaica in 1973, made lightwork of the newly crowned ‘grunting and always coming in’ ox of a title-holder, Smokin’ Joe Frazier. As the young ‘King of the Big Men’, Foreman was not only unbeatable. He was indestructible. He fought and he decimated. That’s how he rolled, a shade of the later champion Mike Tyson.

Life in the fast lane was easy. The trappings of glory were there, and Foreman partook of all that came his way. It had been hard-earned through talent. But lurking around the ring and in his mind was the teasing, poking Ali. The man who was exiled for his beliefs as a black man, and stripped of title without ever losing, dubbed all those who followed him to the title as imposters. He wanted back what he considered was his and was robbed from him. Frazier sent him down and out to defend his title, but Foreman’s smashing of Smokin’ Joe gave Ali a new target. He was forever trying to mock George into giving him the challenge. After a long wait, Foreman gave in, because he did not see the ageing, slowing, rusty Ali as threat, but also for reasons of vanity to shut “the lip” and, of course, for the big purse. What a bluff artist Don King contrived as “rumble in the jungle” and wangled out of Zaire dictator Mobutu is the stuff of legends, creating a 10-million dollar prize, and much more, out of nothing in his pocket.

Lou Savarese of New York City blocks a right from George Foreman (AP Image)

The fight lived up to its billing. And has remained the poster of victory of the underdog and of resilience. Ali played on Foreman’s mind, rallied the fawning crowds behind him, and tricked Foreman with ‘rope-a-dope’ – he retreated to the ropes and the angry man worked on his belly for round after round, and drained himself of strength. Ali had set him up, and then despatched him with ease. In the video, you see foreman going down in a swirling circular motion, and Ali with fist cocked does not interrupt his fall with another punch. Norman Mailer, in The Fight, said it was as if Ali did not want to spoil the aesthetics of the knock-out.

When Foreman fell, he hit the bottom. An older and slower Ali had beaten the man who brooked no challenge and whose punch was known as the death blow. It was supposed to have been a walk in the park, but became a slow march to the mortuary.

Boxing is known for the clashes that define the sport and its practitioners. And Ali became the curse of the golden generation of fighters. He became the measure of greatness, and all had to go through him. There was no escape. As Bobby axelrod in “billions”, the ott tale of intrigues about Stock Markets, says to “the Attorney” who is forever looking to trap him, “Why are you always after me? I know, there are fights that one measures himself against, fights that take more out of you than winning can ever give you. Ali had Frazier. You …..” It was that kind of trap that Ali set up.

The best of the fighters were robbed of their greatness, because Ali loomed over them. His trilogy with Joe Frazier, his twin defeats of Sonny Liston, his landmark rumble against Foreman became the ghosts that haunted the rivals lifelong. Not just in the ring, but Ali, for purposes of social messaging and mind games, and for plain hyping for Gatemoney, robbed the rivals of their blackness by painting them as Uncle Toms, and of their humanness by mocking them as Ugly Bear, Ignorant and Gorilla. And it embittered them. Frazier was cursing all his life, till his death.

Post-Zaire, Foreman was lost. He experienced a down that sent him searching for meanings in his existence. He boxed for a while to prove he was more than “rumble”. But then, the inevitable happened. He realized he was lost. And like it happens with men looking for reasons in the wilderness, he found God. He took to preaching. He changed. Then, cheated by his partner, he could not muster money to carry on his ‘youth centre”, and had to do events as Foreman the Boxer, to generate funds. And then, the epiphany. If he had to make money by playing the boxer, why not get in the ring and make a lot, and at once. From there emerged the dream of winning back the title.

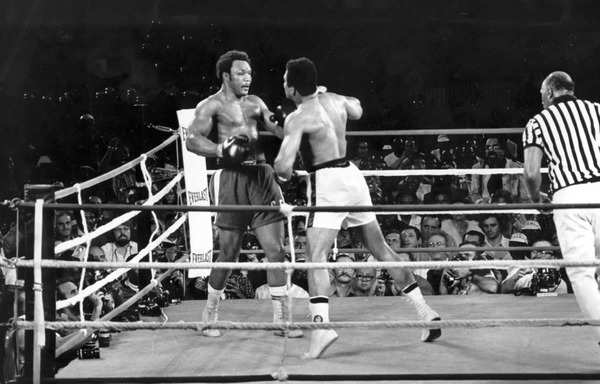

Defending world heavyweight champion George Foreman, left, watches a right from challenger Muhammad Ali (AP Image)

He went to Dundee who, as Ali’s trainer, had played a part in his life-altering Zaire defeat, and asked Dundee to be his corner now. Foreman, as he revealed later (dittoed by the trainer himself) told Dundee that he remembered how Ali was taking it lightly in Zaire, and he was getting on top, before Dundee shouted “don’t play with that sucker!” Immediately, Ali stopped clowning, and got back to boxing. “I have liked you since that moment,” Foreman said. The two bonded. There was surprise in the press about an old ex-champion coming back to try win the title again. It generated mirth, given the bald, fat Foreman. With boxing littered with tales of lust for one last shot at glory in old age, people did not take him seriously. But serious, Foreman dead was. As Dundee reveals, Foreman on his comeback trail trained harder than any young man. He had a pick-up truck chugging on the road, with a heavy bag dangling at the rear, and Foreman punching it, all the while going forward.

It so happened, Evander ‘the real deal” Holyfield, failed to knock out Foreman, but won on points. Yet, for the preacher, glory was pre-destined. By a quirk of fate, Moorer knocked out Holyfield in a shock result, and one particular vacant boxing belt in the World of alphabet soup of titles saw Foreman challenge him. What followed was history, with, after round 13, the belt adorning Foreman’s bulging waistline once again, after a gap of 20 years.

Few lives end on top, and fewer at summit lost decades ago. Foreman managed it. He was also blessed with health. He punched hard and a lot, but rarely took them. So, he escaped the conditions that afflicted many heavyweights in later life. He reinvented himself as a businessman, lending his name to Grills and other contraptions. And lived with his fifth wife, and kids and grand-kids in Texas. The world remembered him, as he made frequent pitstops on sports channels, entertaining the same questions about ‘rumble’, Ali, boxing, contemporary fights, in between slipping in the promotion of his products.

But one thing stood out in his rediscovery of self. Questions about Ali, his nemesis to whom his being and his glory got hyphenated with forever, never shot up his bile. He, instead, remembered him with reverence — “Ali was bigger than boxing”. He did not shy away from the fact that others, blacks like him, were just great practitioners of their skill, while Ali was a freedom fighter, black pride, who was also a pugilist.

That appreciation of his nemesis revealed that Foreman, in his second coming, did become a child of God. Calm, honest, shorn of vanity. Truthful. And that’s why, this Saturday, he went away happy.