A steep, narrow, barely lit staircase leads to Vinubhai Parmar’s rooftop room in Surat. Inside, folding beds and scattered kitchenware hint at a life in distress. His teenage sons, Shivam and Dhruv, sit cross-legged on the floor, doing their homework. At 18, Shivam has come to terms with the upheaval at home after his father, a ratna-kalakar or diamond polisher, lost his job in early July. Dhruv, in Class VIII, is undeterred. “I will keep studying. I want to be a computer engineer,” he says.

Parmar, 47, is desolate. In 2005, he left Bhavnagar, a district in Gujarat’s Saurashtra region, for Surat, looking forward to a bright future in its booming diamond industry. Those hopes have now turned to dust. “I don’t know how I will continue my children’s education. We are barely managing to afford two meals a day. I had to borrow from friends and family,” he says. After nearly two decades of polishing gems, he says, “All I see is darkness.” Surat is India’s diamond capital. The city processes 90% of the world’s rough diamonds by volume. But the light has gone out of Surat’s diamond streets. Now, the import of rough diamonds has plummeted due to weak global demand.

Surat is grappling with factory closures, job losses, distress and suicides due to dwindling orders and falling prices. The growing presence of companies manufacturing and polishing labgrown diamonds (LGDs) in the city is further complicating the landscape.

Lack lustre

“Mandee”, recession, is the word on everyone’s lips in the diamond trade hubs of Mini Bazar, Choksi Bazar and Mahidharpura Hira Bazar in Surat. As diamond polishers face job losses or drastically reduced work hours, employers blame the wars in Russia-Ukraine and West Asia, and LGDs that are further squeezing the profit margins.

According to Jagdishbhai Khunt, president of the Surat Diamond Association , which represents manufacturers and traders, nearly half of the diamonds polished in Surat’s factories are now lab-grown.

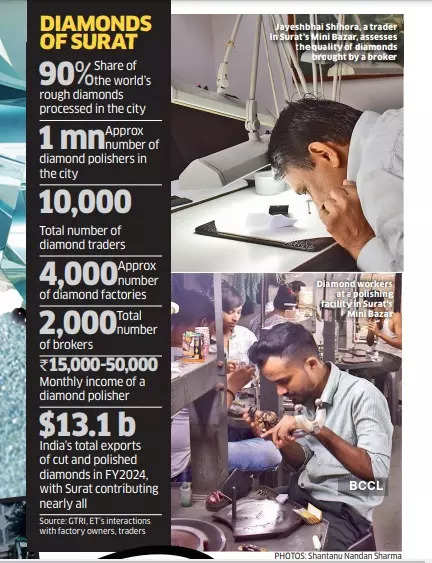

Surat’s diamond industry employs nearly a million people. The city is home to about 4,000 diamond factories and supports an extensive network of 10,000 diamond traders and 2,000 brokers. In terms of value, the city contributes about one-third of global diamond exports. Other pockets in Gujarat such as Bhavnagar, Rajkot, Amreli and Ahmedabad are also traditional centres for cutting and polishing gems. On either side of the main street in Mini Bazar, ET came across street vendors who have either lost their jobs or quit their work in diamond polishing due to falling wages. “You will find many vendors like me who earlier worked in diamond factories. Most of them would now say, ‘Enough of being a ratna-kalakar,’” says Prakash Joshi, 42, who now sells phone accessories. “Some have taken up jobs as delivery boys of Zomato and Swiggy. With duplicate diamonds [he means lab-grown diamonds] dominating the market, riding out this mandee will be difficult.”

On the same street where he polished diamonds, Dipak Ghetiya now sells ghughra, a popular Gujarati snack, for Rs 30 a plate. The 38-year-old has named his food cart “Ratnakalakar Nasta House”, a throwback to his days in the diamond industry. “Until last Diwali, I was earning Rs 40,000-50,000 a month from polishing. But my income plummeted quickly. By June, I was getting just Rs 15,000. That’s simply not enough to survive in a city like Surat,” says Ghetiya. He and his wife Jashoda have started uploading Gujarati recipe videos on YouTube, hoping to showcase their culinary skills to a wider audience and create an additional source of income by monetising their content.

Falling demand

Describing the current situation as deeply troubling, Bhaveshbhai Tank, vice-president of the Gujarat Diamond Workers’ Union, says the union has submitted a memorandum to the Gujarat government, seeking an economic relief package for those who have lost their jobs and for the families of workers who have taken their lives. “About 70 workers have died by suicide in the past 17 months,” he says. ET could not independently verify this figure. Surat Diamond Association president Khunt cautions against attributing every suicide to hardships in the diamond industry, although he concedes that there could have been “some suicides among the 10 lakh workers”. He says reduced working hours and layoffs have been driven by decreased demand for diamonds in major markets like the US and China.

There is no precise data on factory closures and job losses in Surat, but anecdotal evidence points to a major wave of layoffs in the first week of July. The crisis, though, has been unfolding since the beginning of 2023. Several small factories, typically housing 20-40 ghantis, have shuttered their doors, at least temporarily. A ghanti is a round table around which four diamond polishers work simultaneously.

Data from the ministry of commerce and industry reveal the stark realities in the diamond industry. According to a report released last month by trade think tank GTRI, which analysed the ministry’s data, rough diamond imports declined 24.5%, from $18.5 billion in FY2022 to $14 billion in FY2024, reflecting weak global markets and falling orders. After adjusting for re-exported rough diamonds, net imports fell by 25%, from $17.5 billion to $13 billion, underscoring diminished demand for diamond processing in India. The report further highlights the gap between net rough diamond imports and net cut-and-polished diamond exports, which widened from $1.6 billion in FY2022 to $4.4 billion in FY2024. This indicates a significant inventory build-up and insufficient export orders.

Inventory piling up

To understand the market dynamics, this writer went to Bhurakhiya Impacts, a diamond polishing factory with 30 ghantis. Hitesh Dholiya, who set up the facility seven years ago, says demand has turned lukewarm. “These days, I’m only calling in 70-80 workers, even though I have seating arrangements for 120,” says the 42-year-old. Gesturing toward rows of small packets filled with diamonds, he says, “Look at them. Where will I store them? With prices falling, the inventory is piling up.”

Both Dholiya and Jayeshbhai Shihora, a veteran trader who has been in the diamond business for 30 years, say lab-grown diamonds have shaken the industry. On the one hand, prices of natural diamonds have softened, and on the other, Shihora says, value of LGDs has steeply declined over the past two years. He says the polishing process and the labour cost remain the same whether the rough diamond is mined in Botswana or Russia, or grown in a lab in Surat. He says the cost ratio between lab-grown rough diamonds and natural rough diamonds is 1:10, while the final product price of a lab-grown diamond could be 70% lower than that of a natural diamond, depending on its quality. Yet, they are so visually alike that neither a manufacturer nor a seasoned trader can distinguish between the two without specialised machines. Meanwhile, a 65-year-old broker named Bhikhabhai Vaghani walks in, carrying diamonds from a small factory owner, to meet Shihora. The gems are wrapped in white paper. Shihora adjusts his table lamp and puts on his glasses to assess the quality of the gems.

“It’s No. 3 maal,” says Shihora, noting that it could fetch Rs 15,000-16,000 per carat. Since he currently has no customers for diamonds of that grade, he politely declines the broker’s offer. In the market, transactions occur both in cash and on credit, with the broker earning a commission of 1% from the seller. Diamonds are assessed based on their clarity, denoted by codes such as IF (internally flawless), VVS (very, very slightly included, referring to inclusions or blemishes) and VS (very slightly included) as well as colour, graded with letters like D, E and F. “A diamond with IF clarity and D colour is the finest. It is traded for approximately Rs 90,000 per carat. Once it reaches the retail jewellery market, the price could soar to Rs 1,30,000,” says Bhagwan Bhai, a broker.

In the Union budget presented in July, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman proposed the introduction of “safe harbour rates” for foreign mining companies selling raw diamonds in India. It was aimed at reducing the reliance on intermediary nations and securing raw materials at more competitive prices.

Currently, Dubai, despite having no domestic diamond production, supplies 65% of India’s total rough diamond requirements, according to figures from April to June 2024.

While such measures may promise long-term relief to the beleaguered industry, workers like Maheshbhai Poriya remain apprehensive. He is not sure when demand will rise and his job will be restored. For now, the 45-year-old, unemployed ratna-kalakar is relying on the modest income his wife , Kanchanben, and their elder daughter, Nancy, earn from embroidering saris. He is waiting for the diamond trade’s lost lustre to shine once more.