MUMBAI: In much of rural India, families continue to light their kitchen fires with wood, dung and coal – a practice that exposes them to harmful smoke.

Switching these families to exclusive use of LPG, a relatively clean energy, would save more than 1,50,000 lives a year due to reductions in both indoor and outdoor pollution, according to a new study by Vital Strategies, a global public health organisation.Such a transition would also add around 37 lakh “healthy years” to the population, the study found.

More than half these benefits would be in four states – Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, West Bengal, and Madhya Pradesh. These states have a combination of the highest populations, lowest LPG use, and highest ambient air pollution, said Sumi Mehta, the epidemiologist who led the study at Vital Strategies. “They have everything going on at the same time.”

Most of the health gains come from reductions in infant mortality due to low birth weight among children under five as well as improvements in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among people over 60, the study said.

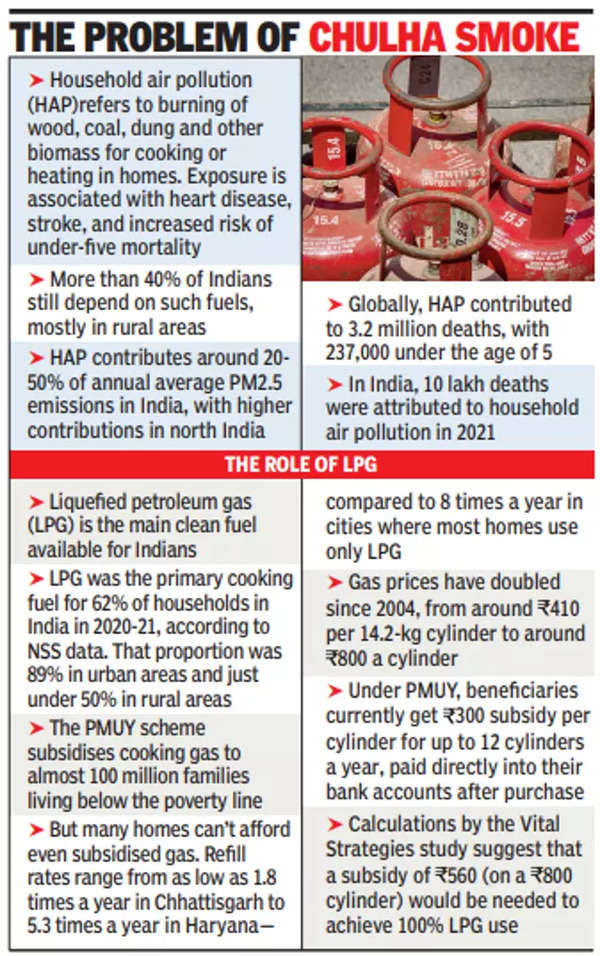

The findings support a health-based targeting of the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY), govt scheme providing subsidised gas to families below the poverty line. For this study, researchers looked at how partial and full LPG subsidies would impact the health of some 90 million poor households that currently have either no access to cooking gas or partial access under PMUY. If such families were to switch to LPG exclusively, average household exposure to the pollutant PM2.5 would fall dramatically, the study estimated – from 180 ug/m3 to 48 ug/m3.

Reductions in PM2.5 exposure would not be restricted to those homes, however. Because “chulha” smoke contributes to ambient air pollution, the LPG intervention would also reduce ambient annual average PM2.5 levels, ranging from a 4% decline in Telangana to a 28% drop in Bihar, the study found.

States such as Maharashtra, Odisha, and Uttarakhand would reach national clean air guidelines of 40 ug/m3, the analysis found.

The study assessed the annual cost of full subsidy for a household to be Rs 8,800 a year, for eight cylinders assuming a price of Rs 1,100 a cylinder. A partial subsidy would mean spending Rs 4,800 per household in a year at the rate of Rs 600 a cylinder. For homes not under PMUY, subsidies would have to include an additional Rs 2,000 per household for connection cost.

The study estimated the cost per death averted would range from around Rs 15 lakh for fully subsidising pregnant women households to Rs 62 lakh for general households. The cost-benefit analysis for all the scenarios met the WHO threshold for a health intervention, the study said.

Health researchers increasingly see reducing “chulha” smoke as critical to solving India’s air pollution problem. “You’re not going to reach national air quality standards without eliminating emissions from the household sector,” Kalpana Balakrishnan of Shri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research in Chennai said.